By Amit Kapoor, Pradeep Puri and Ananya Khurana

Indias Millet Moment: A Holistic Shift from Paddy to Sustainability

As the world turns its attention to sustainable agriculture, millet is emerging as a promising alternative to paddy production in India. Globally, the millet market is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6.2% from 2024 to 2030, while the Indian millet market is projected to grow at a CAGR of approximately 16% in the same period. With increasing global and national interest in millet, now is the perfect time for policymakers to efficiently create a conducive and cohesive ecosystem for higher millet production in India. But for an effective transition, the farmers, who are the Karta-Dharta (true stewards) of Indian agriculture, need to be brought into confidence.

As of now, paddy has the largest area under cultivation in India, and agricultural input subsidies are skewed towards paddy production. For instance, fertilizer usage in major paddy-producing states such as Punjab (248 kg/ha), Andhra Pradesh (247 kg/ha), Telangana (220 kg/ha) and Haryana (214 kg/ha) has been above the national average (145 kg/ha), in recent years. Thus, the government’s expenditure for supporting paddy production and procurement specifically in Punjab and Haryana, the paddy-producing states with the highest per capita income, is approximately thrice the gross profit earned by the paddy farmers of these states. As a result of this, India over-produces paddy. Due to overproduction, the prominent paddy-producing states of India are experiencing a depletion of their natural resource base, further propelling climate change. Thus, continuing paddy production in these states at the current scale seems unsustainable in the long run. Instead, the farmers of these states should shift their attention and resources towards higher millet production. However, acknowledging that Indian farmers might be apprehensive about changing their agricultural practices reiterates the significance of adequate incentives that could encourage them to shift from paddy to millet production.

Firstly, the paddy farmers should be encouraged to cut back on paddy production. For the same, they can be offered upfront cash incentives for not producing paddy. Subsequently, the government can save on agricultural input subsidies and paddy procurement costs, which can then be utilized to incentivize millet production. The savings can also be reinvested in farmer-oriented awareness programs, promotion of crop diversification, agricultural digitalization, infrastructural upgradation for crop storage, agro-processing for value addition, and management of post-harvest losses. This would further imply that the government would not have to bear any additional cost burden. However, ensuring that the financial incentives remain cost-neutral for the government while providing adequate support to farmers is a delicate balance. To strike this balance, the government should resolve issues regarding farmers’ awareness of sustainable agriculture, digital literacy, financial inclusion, access to banking services, internet connectivity, and administrative efficiency in monitoring and evaluating the implementation of the incentive mechanism. This would avoid financial leakages and ensure timely transfer of funds for efficient resource use, unlike subsidies that usually result in the overuse of inputs. Eventually, the chances of an ecological disaster in the paddy-producing states, especially Punjab and Haryana, could be minimized. Such initiatives could also support the commercialization of millet production, subsequently changing the overall sentiment of the market in favour of millet.

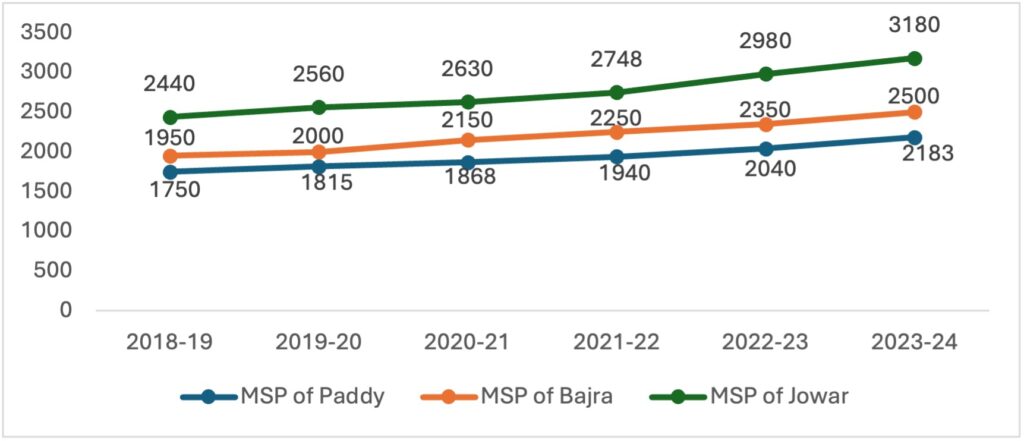

On the other hand, the minimum support price (MSP) offered on millet crops such as bajra (INR 2,500 per quintal) and jowar (INR 3,180 per quintal) is already higher than the MSP offered on paddy (INR 2,183 per quintal) and the trend has been consistent in the past couple of years (Figure 1). The government has also rolled out a couple of schemes to promote millet production and consumption, highlighting its high nutritional value.

Figure 1: Minimum Support Price of Paddy and Millet in India between 2018-19 and 2023-24 (in INR/Quintal)

Source: DES| MSP- Paddy & Millet

Yet, paddy production dominates Indian agriculture, especially in the Indo-Gangetic Plains of the country. This can be attributed to the limited demand for millet compared to rice and thus, policy provisions that favour paddy production over millet production. For instance, the government of India ensures the procurement of paddy at the MSP through agencies like the Food Corporation of India (FCI). As a result, the paddy farmers receive a guaranteed price for their produce. This reduces the risk of market price fluctuations and ensures a stable income for them. Moreover, as rice is a staple food for a significant portion of the Indian population, the PDS plays a crucial role in distributing it to the poor at subsidized rates. Therefore, rice has a consistent demand that further implies a stable market for paddy production. Meanwhile, despite its nutritional benefits, millet is not as popular among consumers due to a lack of awareness about its health benefits. This subsequently leads to lower demand for millet, compared to rice. As a result, millets do not have a robust and assured procurement system. Specifically, the off-take of millet such as Bajra and Jowar from Punjab and Haryana, lying in the Indo-Gangetic Plains of India, is minimal, compared to the off-take of paddy from the states. In 2022-23, while 18.21 million tonnes of paddy was procured from Punjab and 5.94 million tonnes of it was procured from Haryana for the PDS, the off take of Bajra and Jowar ranged between 0-140 tonnes only. Furthermore, there are insufficient policy initiatives that promote fortified millet varieties. Besides this, though the MSP of bajra and jowar increased between 2021-22 and 2023-24, the production of the millet and the area under its cultivation experienced a lower CAGR compared to the MSP (Table 1). Therefore, MSP on millet in its existing form, along with the allied measures for support, is inadequate to markedly transform millet production in the country.

Table 1: CAGR of the MSP, Production and Area under Bajra and Jowar in India (2021-24)

| Millet | CAGR of MSP | CAGR of Production | CAGR of Area |

| Bajra | 3.57% | 3.11% | 2.57% |

| Jowar | 4.99% | 4.53% | 2.40% |

To keep up the fervor for millet production, in addition to the cash incentives offered to the farmers via a direct benefit transfer mechanism, the farmers should also be offered adequate price support on millet. The government savings, net of cash incentives given to the farmers can be utilized to offer a higher MSP on millet and assure its procurement by the FCI.

As a step forward in the right direction, the Indian government has already offered to increase the MSP on Bajra by 77% to INR 4,375 per quintal in 2024-25. This could help the farmers double their income in just a few cropping seasons, with the fastest impact projected in the top millet-producing states of India, such as Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh (Table 2).

Table 2: Impact of a 77% Increase in MSP of Bajra on Farmers’ Income

| MSP of Bajra (INR/Quintal) | Farmer’s Income (INR/ha) | |||

| Punjab | Haryana | Rajasthan | Madhya Pradesh | |

| 2500 | 60692.82 | 64498.76 | 13492.2 | 29798.21 |

| 4375 | 74192.82 | 114522.8 | 39712.66 | 85566.57 |

| Change (%) | 20% | 77% | 94% | 287% |

Likewise, if the MSP of Jowar also increases by say, 50% from INR 2980/Quintal to INR 4470/Quintal then on one hand, the income of the farmers can increase by at least twice in Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan to INR 59633/ha and INR 23880/ha, respectively. On the other hand, farmers in Haryana earn more from Jowar production compared to those in Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan. So, a 50% increase in the MSP for Jowar would increase farmers’ income in Haryana by 12%, which is a smaller percentage increase but effectively, their income would rise to a higher level of INR 72,340 per hectare.

The FCI can play a pivotal role in boosting millet production by ensuring assured procurement of Bajra and Jowar at MSP. This would provide farmers with a guaranteed market and stable income, encouraging them to cultivate these crops. Currently, millet procurement is limited and inconsistent. By increasing procurement, the FCI can help stabilize prices and reduce the risk of distress sales. The Production Linked Incentive Scheme for Millet-based Products (PLISMBP) for the period FY 2022 to FY 2026 should be scaled up. On the other hand, the Public Distribution System (PDS) has a crucial role to play in boosting millet consumption. Last but not least, the Department of Food & Public Distribution can collaborate with NGOs and educational institutions to further promote millets through workshops, seminars, and media campaigns. As of now, India ranks among the top five millet exporters worldwide but contributes only 2% to global exports. Nonetheless, as the market size of millets is expected to exceed USD 14 billion at a CAGR of 4.6% between 2019-2027, India must strengthen its millet value chains and enhance millet export to reap the benefits of this opportunity and enhance its economic welfare.

A comprehensive approach is thus needed to truly transform millet production in India. The provision of cash incentives for millet production in conjunction with a higher MSP for millets, better procurement infrastructure, and awareness, along with policy support and encouragements like carbon credits for sustainable farming practices, should be considered. The potential payoff? Doubling farmers’ incomes within just a few cropping seasons. This holistic approach not only promises economic benefits but also paves the way for a more sustainable and resilient agricultural future.

The article was published with Business Standard on April 30, 2025.